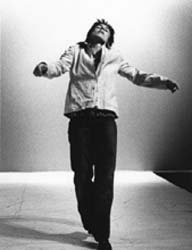

Alcalá de Henares, an old half-ruined church, reformed and converted into a performance space. Three performers come to meet the spectators when they enter the space, empty, “forbidden to sit”. At a transept’s corner, the sound and video control. Somewhere among the pillars that divide the naves, Olga Mesa, the choreographer who looks at. Once the entrance has been closed the performers start quietly their work: measuring the space in relation to their own bodies, surprising themselves over and over by the articulation of the limbs, by the infinite possibilities of watching upon oneself, without ever reaching the state that would lead to the unity of looking and being. Meanwhile Olga Mesa observes. The spectators also observe: bodies at times erect, at times naked, at times laying on the marble floor, or retreating to the remains of the altar, where they search for a intimacy in dialog with a tiny camera. The images of their faces in the intimacy, or those of the bodies in the public space of the church recorded life, camera in hand, by Daniel Miracle.

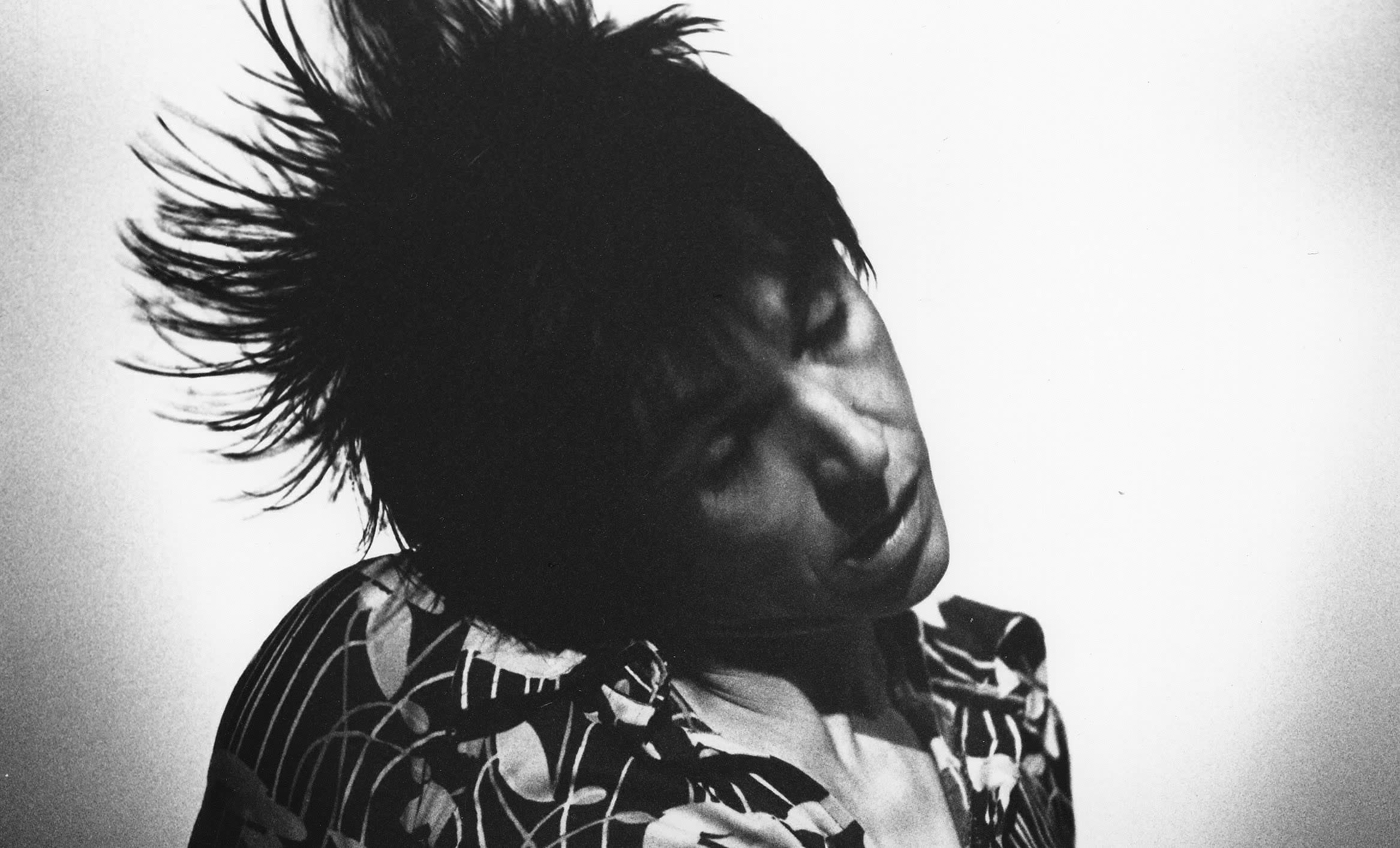

Some months later Más público, más privado (2001) was presented as the closing of the last edition of Desviaciones, at the theatre of the Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid. The ecclesiastic attempt had become by then a theatre piece. However the performers kept on watching. Sited among the audience they awaited their turn to perform. Serenely they would go onto the stage, give themselves up to a solitary reflection and return to their place among the audience, though not for a long time. At a certain moment the four of them (in this occasion the choreographer also performed) occupied the stage and started a game of falls, tumbles, accidents, disturbances and apologies… A bit later, naked, they totally ignored the public’s watch that scrutinised their movements and intentions. Watched even when outside the stage, thanks to a peeping monitor that transmitted images from a handycamera: grimaces, laughs, body fragments, skin…

Making the spectator aware of his condition of voyeur, Olga Mesa preserved herself from objectuality. Saved her own glance from objectuality and forced the spectator to an intellectual/emotional action that goes beyond observing. Thus, the watch becomes an element of the performance and not its aim. This was something she already started to explore with Daisy Planet (1999), a short solo where, for the fist time, she used the Neokinok designed by Daniel Miracle (a kind of portable TV station that allows life editing of images). Since the beginning of the piece, the audience notices that their image is being filmed by a micro-camera placed at the back of the stage, and exposed in a monitor at the proscenium. The choreographer could also address to the back wall, and while keeping her back to the audience, offer them a close up of her face on the monitor. Dissociating the facial (mediated) expression from the corporal (live) one, exposing thus the complexity of a body / human endowed with a its own right to look.

“I think with the eyes as moving elements”, wrote Lisa Nelson “ I think with sight […] I think with movement and sight”. And the natural consequence of this shift of the thought to the sight is the incorporation of the camera into the choreographic process. Incorporation: to make the camera part of one’s own organism, to adapt the movement to that new sight controlled by the hand. “I observed my body adapted its shape depending on the function of the camera I was holding in my hand; like the hand of a baby is modelled by the shape of the cup it holds”. “From time to time”, confessed Nelson, “the needs of my body took over the function of the filmmaker”. (…)

José Antonio Sánchez.

Performance Research vol. 8 nº 4 (“Moving bodies”, december 2003), pp. 92-99